Watch on the page for photo galleries to see additional photos – look for the arrow on right side of page

WHY DO OTTERS PLAY –OR DO THEY? RIVER OTTER (LUTRA CANADENSIS)

December 2013

Helen Maria Darker and Bill Darker sent this photo and report:

At dawn we watched for about 10 minutes as the otters swam and played on the ice. The ice bits sank a bit when all 3 were on a small piece of ice.

We would not have seen them except for a large bird which flew down -the Bald Eagles had come again –must have been fish there.

The Darkers live on Sparrow Lake.

Otters appear to engage in various behaviours for sheer enjoyment, such as making waterslides and then sliding on them into the water.

These photos of waterslides, taken some year ago, near the edge of a beaver pond in Severn Township, seemed to have been used often.

This was probably a favourite place to slide into the water, on their bellies, partly propelled by their feet, as if on a skateboard.

It is thought that they usually do not climb to the top of a slope for another slide. Is this play or just low energy travel?

In 1983 2 researchers recorded 294 observations periods. Play behavior was noted in only 17 (6%) of these observations.

However, otters’ playful reputation is famous.

Photos of the otter slides and text by Nancy Ironside

November 2013 Crossing the North River in Severn Township:

The North River flows from Bass Lake to Matchedash Bay, in a meandering way, with shallow channels, draining the clay flats of Severn Township. Parts of the broad valleys are still swampy, especially as it leaves Bass Lake, upstream from Marchmount, and as it enters Matchedash Bay. “It is probable that it was once even more sluggish, since the water level of Georgian Bay has fallen over 9 feet in the last 300 years, as is indicated by investigations at Fort Ste Marie, on the Wye River near Midland”. Parts of the river can be paddled, although progress is slow because of obstructions, for example barbed wire fences. We decided to trace its course in Severn Township, crossing over about 20 bridges.

The river leaves Bass lake, crosses Horseshoe Valley Road, then Highway 12, and we pick it up as it crosses into Severn

Township at the Town Line, before heading to Marchmount with its dam and mill.

October 2013 Grifola frondosa – Hen of the Woods

|

|

|

Many people travel across Canada, or even to other continents, in search of mushrooms, but these were found about 40 feet from my front door, at the base of 2 living oak trees. While it may not have been the most rare, or the most colourful, it certainly caused the most comment at the fall mushroom foray, where it sat, welcoming the participants at the check- in. At the cook-up 50 people fed from this September specimen. It is a favourite edible for many people, and hard to mistake for anything else.

There were 5 in total, all weighing about 8 lbs. The first 2 were found mid September and the other 3 were found, on another big oak tree, in mid October, on the same tree where one was found 2 years ago.

There are many very large old oaks on or near my property in Orillia. The mushroom fruits on the ground from roots at the base of

various living trees, but most commonly, near oaks.

Trees are symbiotic with one (or many) fungi. The fungus gets organic nutrients – mainly glucose and fructose – from the tree roots, a result of plant photosynthesis. Fungi collect nitrogen and phosphorous, among other chemicals, from the soil, and pass them to the plant. The hyphal network increases the absorption area by up to 40-fold.

It has been postulated that the Grifola frondosa may have been living symbiotically with the oak trees for years, without fruiting. It is a “good parasite”, not killing its food source, but keeping it alive as long as possible, in order to maximize its own life. It is possible that the fungus sees that its symbiotic partner is nearing the end of its life, and so sends up this wonderful fruiting body, full of spores, to look for another partner. This is an unproven hypothesis – but DNA of the soil may eventually prove this interesting concept correct.

In the long life of an oak, this impending death could be 10 or 20 years away, so we can expect to collect for some years to come.

September photo by Joyce Fisher

September 2013 Pectinatella magnifica – a Freshwater Bryozoan

|

the broyozoans have been around for 450 million years. One individual replicates many exact clones to form their colony, yet they change their dna for the next generation. |

|

one washed up on the rocks. Very dense jelly! |

I ( Shelley Morrison) came across these fascinating creatures while out on a canoe paddle with the family. We observed them attached to many rocks throughout the river in the Severn area. We were puzzled by what these gelatinous creatures could be so we decided to do some research and this is what we’ve found! We were paddling near Turtle Lake, off Swift Rapids Rd. The water was about 5 feet deep and they were around 6-10 inches under the water.

Bryozoans are microscopic aquatic invertebrates that live in colonies. The colonies of different species can take on many different forms. Most are attached to a structure such as a rock or submerged branch. Some colonies are rounded, jellylike masses. Others resemble antlers or mosses (bryophyte means “moss animal”), trace delicately like vines across rocks or create furry colonies. The species that creates the round, jellylike masses is Pectinatella magnifica which is the species I had come across.

Marine bryozoan fossils have been dated back to 480,000,000 years. There are currently around 5,000 species known today and 15,000 species that have been fossilized through the millennias. The species that we found, P.Magnifica, is one of only a few freshwater species and are virtually unknown as fossils, presumably because they did not have mineralized skeletons.

Each tiny individual bryozoan (zooid) is attached to a surface at its base.

Its body has an outer sleeve like structure (cystid) and a mass of organs (polypide) that moves within it. An opening at the top of the cystid permits the polypide to slide outward toward the water, exposing a head like structure (lophophore) crowned with tentacles, which filter food from water. At the slightest disturbance, the polypide and tentacles retract instantly.

Bryozoans eat microscopic organisms such as algae, protozoas, and are eaten by several larger aquatic predators, including fish, insects and snails. Like mussels and other filter feeders, they gradually cleanse the water as they feed. Their presence usually indicates good water quality as they are unable to thrive in contaminated water.

Bryozoans can reproduce in several ways. Zooids can “clone” themselves by budding, which creates these colonies, but each zooid contains both eggs and sperm and can reproduce sexually. Larval forms undergo complete metamorphosis. In their bodies, freshwater bryozoans form hard, round statoblasts, which function like seeds. During the fall season when the water temperature drops below 6-8 degrees Celsius, the colonies break apart and die, but the dissolving zooids free the statoblasts, which can disperse widely. These endure until the weather is warm enough for them to resume their life cycle. Each of the statoblasts have small hooks on them which provides an opportunity to hitch a ride on fur or feathers, to a new water source.

Shelley Morrison sent us this amazing find -photos and text.

August 2013 DeKay’s Brownsnake Storeria dekayi

The DeKay’s Brownsnake is normally secretive, hiding by day and coming out at night to feed on snail, slugs and earthworms. On August 4, a cool day, at about 10 am, we found this little snake (about 10 inches long), curled up, basking on the warm asphalt at the beginning of the Uhthoff Trail, going north from Coldwater. Even when we placed the quarter (for size comparison) beside him, he did not move, nor did he move when others walked by. In this area the trail passes by the backs of houses, where there would be woody debris or leaf litter for him to hide under. He was gone by noon when the day had become warm.

The Dekay’s Brownsnake is fairly common and widespread within its Ontario range. This species is not considered at risk in Ontario and the Global status lists it as Least Concern.

If you are interested in Citizen science and would like to help with the Reptile and Amphibian Atlas for Ontario you might be interesting in an app

for your smart phone. Ontario Nature is sponsoring the Reptile and Amphibian Atlas app which identifies Ontario’s reptiles and amphibians,

lets you submit sightings with ease and stores a record of your submissions.

The new app:

- Identifies more than 50 species of reptiles and amphibians that can be found in Ontario.

- Provides a description of each species along with colour photos, and a range map.

- Has an easy-to-use tool to submit a sighting to the Ontario Reptile and Amphibian atlas. Uses your phone’s internal mapping software, camera and clock to allow you to submit sightings in less than 30 seconds while out in the field.

- The app is available for the iPhone and other apple devices on the iTunes store for free A version for Android devices is available for free on the Google Play Store

Catherine Jimenea from Ontario Nature reports that “The app is doing quite well with over 700 users and over 1600 observations. Out of the 1600, around 20 of them are of the Dekay’s Brownsnake”

Photos by Heather Ewing

July 2013 Caspian Terns on Sparrow Lake

July 2012, terns looking left, one Herring Gull , looking right. July 2013

This large noisy tern, with a large red beak, can be seen patrolling our local lakes (Sparrow, Couchiching, Simcoe) for fish, after they are fledged, by July. Ours birds are considered to nest in the Georgian Bay Islands, (where they are away from predators, ) along with Ring-billed Gulls. They may fly 50-60 kms from their nesting site to fish. They do not nest on Gull Island in Sparrow Lake, although they commonly roost there.

The Canadian Wildlife Service regularly monitors the islands on Lake Huron for colonial nesting birds. This is a challenge, since the scientists have to cope with the smell, the millions of little bugs and the attacking terns.

Photos by Bill Darker, taken near Long Island (” The tern sanctuary”) on Sparrow Lake

June 2013 Orange-fruited Horse Gentian Triosteum aurantiacum.

In spite of its name, it is not a Gentian, but rather in the Honeysuckle family (Caprifoliacea)

This uncommon, native plant, over a meter high, has long paired leaves, dull purplish flowers, at the axils and bright red orange berries. It flowers in June, but is often overlooked because of the abundance of other plants and colours, but in October, when the orange berries come out at the leaf axils, many people notice it.

It grows in forested areas, but, for some reason, we find it more commonly in Carden. The origin of its common name is unknown, maybe related to the medicinal use of a similiar plant in Europe, and “ Horse” may indicate that it is large.

Books:

Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide: 78

Peterson’s Field Guide to Wildflowers: 390 They use the alternative common name “ Feverwort”

ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario: 230

Photos by Margo Holt and Nancy Ironside

May 2013 Nesting Bluebirds

Bluebirds are one of the few grassland species that are increasing, and most people attribute this to nest boxes, that have been placed on fence posts. It is thought that their natural nesting sites (old fence posts and branch stubs) have been increasingly sparse.

In our club Leanore Wiancko and Ray Kiff have maintained box trails, which they monitor every week from April to mid August. The results are tabulated and reported to the Ontario Eastern Bluebird Society each fall.

These photos were taken in the nest boxes on May 26/13 on the trail monitored by Leanore Wianko, with assistance from Kay Prince.

Photos by Leona Beasley. Text assisted by Leanore Wiancko

April 2013 Skunk Cabbage

On April 6, 2013, Alex and I ( Muriel Sinclair) made our annual trek to check out the Skunk Cabbage north of Orillia.

There was still lots of snow on the ground and it was firm enough to carry our weight if we stayed on the packed trail. The Skunk Cabbage was very visible in many places and doing quite well. We noticed little dark circles on the snow … and then a few that had a small hole with frosty ice crystals around the hole. When we peeked in we could see the new plant pushing its way up to the sun.

Perhaps we’ll go back in early May and see the large green leaves that grow as the flower is dying away.

The Eastern Skunk Cabbage- a fascinating plant. It blooms in the wetland areas where the ground is still partially covered with snow, from Nova Scotia and Southern Quebec west to Minnesota and south to N. Carolina and Tennesee. It also grows in Northeastern China and Japan.( The Skunk Cabbage on the Pacific North West coast is a different species, Lysichiton americanus. )

Our Skunk Cabbage is a low growing, foul smelling plant that flowers

early in the spring . The flowers are produced in a 5-10 cm. long spadex,

contained within a spathe, 10-15 cm. tall and are mottled purple in colour.

Only the flowers are visible above the mud, with stems buried below ,

and leaves emerging later.

Skunk Cabbage is notable for its ability to produce heat up to 15- 30 degrees C. above the air temperature, by cyanide resistant cellular respiration, in order to melt its way through the frozen ground. Although flowering while there is still ice and snow on the ground, it is successfully pollinated by early insects that emerge at this time.

Photos and text by Muriel Sinclair.

The plant with the green leaves and no snow was taken May 5/08

March 2013 Snowfleas – Springtails (Collembola) – Hypogastrura nivicola,

(but they may not even be insects.)

This has not been a good winter for warm sunny days, but there was a warm sunny day when this photo was taken March 24/13 – little specks on the snow. Suddenly a speck jumps, and then another. In past years we have found springtails more often and in greater numbers and this second photo is from our collection. On a warm sunny winter day swarms of these minute creatures may be seen on the surface of the snow, or maybe in dense aggregations in a print in the snow, maybe to get shelter from the wind. They have dark bodies which soak up the sun’s rays when they surface. After the snow, they may be all around us, feeding and cleaning up detritus , but we are unable to see them.

They have long forked tails which allow them to make huge giant leaps in comparison to their size, which would be the equivalent of a man jumping over the Eiffel tower. There is a little latch that the fork tail snaps into prior to launching themselves into the air.

But why do they come to the surface? It is postulated that these snow surface aggregations may expedite sexual encounters (although we have never seen any snow fleas interact with another on the snow). Then again, they may be feeding, or they may be looking for new habitats. Since winter active insects graze upon fungal spores and algae, and have full stomachs, they must be protected by antifreeze compounds in the blood ( and they are).

photos by Margo Holt and Nancy Ironside

Information source: Insects: Their Natural History and Diversity by Stephen Marshall.

This lower photo was taken in “Sedge Wren Meadow” on Wylie Road, in a past spring. The black patch in the lower left hand corner, covering the surface of the water was a mass of springtails. We thought these springtails may be washed together in flood debris, but some species live in huge numbers on the surfaces of puddles and ponds. These springtails from the black patch were collected, and were certainly dead by the time we looked at them under the microscope. They may have washed away from their feeding grounds by the spring runoff, or they may be a different species, which live on water, different from the snow fleas we know from the snow. The photo on the right, shows they were dead, lying on their sides, when we checked them under the microscope later.

We have also collected typical “ snow fleas” who lived long enough for us to be able to observe them jumping, under the microscope, as below.

FEBRUARY 2013 RED FOX WITH THE POM POM TAIL

This Red fox was seen hunting in a field in Ramara. When first seen he was stalking something on or under the ground, pounced, then sat to eat his prey. When he became aware of us, he slowly but steadily left. He had a beautiful red coat and black legs, and looked very healthy except for a tail that looked like a rat’s, with a pom pom of fur at the end.

He was not healthy –he had the mange, a skin disease caused by infection with the Sarcoptes scabei mite. The mites are microscopic, somewhat similar to Scabies in humans. Female Sarcoptes mites burrow under the skin and leave a trail of eggs behind. This burrowing creates an inflammatory response in the skin, similar to an allergic reaction. The motion of the mite in and on the skin is extremely itchy. Because the immune system is compromised, the animal becomes lethargic and usually dies of starvation.

I talked to the Aspen Valley Wildlife Sanctuary, which is located about 4 kilometres outside Rousseau. They usually receive 15-20 calls a month about sick Red foxes or Coyotes. If the animal is hanging around a certain area, the Sanctuary will supply treatment with Ivermectin, in pill form,

which can be hidden in meat. They have good success with this, but the fox may be reinfected if he returns to the infected den.

Not a happy story for our beautiful Red fox.

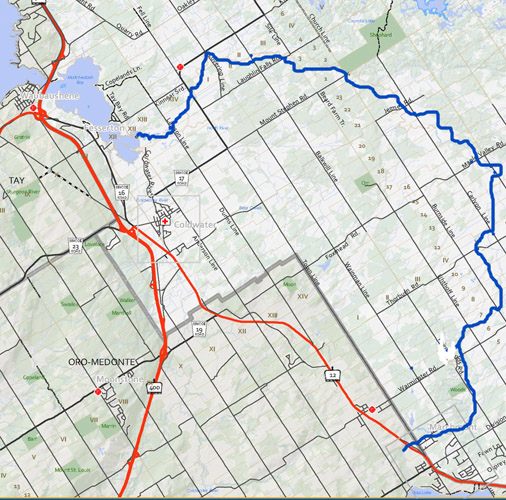

JANUARY 2013 UHTHOFF TRAIL EXTENSION COLDWATER TO WAUBAUSHENE

For many years there have been many rewarding naturalists trips to the east side of Matchedash Bay. Now there is a trail along the west shore –an extension of the Uhthoff Trail from Coldwater to Waubaushene. (There are parking lots near the Beer Store in Coldwater, or near the waterfront in Waubaushene where it connects with the Tay Trails.) The abandoned rail line goes through a cattail marsh as well as wetlands which support water-loving trees like Tamarack and Black Willow. The water level in Matchedash Bay is very low at present, but most of us are hoping for higher water levels in the Great Lakes in future.

Matchedash Bay is one of only two Ramsar sites in Simcoe County; the other being the Minesing Wetlands. A Ramsar site is a wetland of international importance, especially as waterfowl habitat, and is an intergovernmental treaty, that commits member countries to protect wetlands of international importance.

There are 2066 sites worldwide. The convention took place in 1971 in Ramsar, Iran.