Many Bald Eagles are wintering in Ontario, but how do they manage, and why now? December 2014

|

|

|

| Mature Bald Eagle looking for small mammals from the highest perch, inland in Carden near Cameron Ranch Photo by Arni Stinnissen, December 14, 2014 |

Mature Bald Eagle feeding, reflected on the ice at the south end of Lake Couchiching. Photo by Bill and Vicki Sherwood, December 25, 2014 from their balcony at Panorama Point. |

Immature Bald Eagle, entangled in a plastic bag at the dump in Wawa in the winter of 2012. Garbage has hazards. Photo by Arni Stinnissen |

For years no Bald Eagles were found on the Orillia Christmas Bird count, which was started in 1981, and then in 1994, one bird was seen, then another in 1997.

However, since then, there have been Bald eagles in every count in the 21st century, with a maximum of 10 in 2012. This year 4 were found on the count.

This powerful and opportunistic forager feeds on a variety of prey, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, crustaceans, carrion, and even garbage, although fish are preferred. All of this is available in the winter, especially near open water, but the birds are also seen inland.

DDT was introduced after WW2, and was banned in 1972, and the subsequent comeback of Bald Eagles is one of conservationists’ success stories.

Trolling through the Archives of Ontario Field Naturalists this recent upward trend of wintering Bald Eagles is reported from other CBCs, such as:

Arnprior – record high count of 28!

Strathroy –5 birds seen. They comment that prior to 2006 none had been recorded, but they have been seen on every count since.

Port Hope – 5, which tied their previous high.

It is reported from Hamilton that Bald Eagles are on the harbour surfing the ducks. An adult Bald Eagle had a merganser in its talons flying along LaSalle Park last week.

This is a record year for sightings along the Niagara River.

They comment that Bald Eagles have achieved the status of “regular resident” in Niagara

Clearly, there is a remarkable increase in Bald Eagles wintering in central Ontario in recent years. Recovery after DDT and changes due to Global Warming may be the conventional wisdom for this trend, but there may be other causes that are less obvious, maybe unknown.

Geology around “Prairie Smoke”, on the Carden Alvar. November 2014

The Carden Plain can be reached from Orillia by way of Sebright, or by Highway 12, then County Road 46, to CKL #6.To see this rocky outcrop, and to visit Prairie Smoke (a name given to a property donated to the Couchiching Conservancy by Karen Popp), turn north on the west side of Lake Dalrymple, (first turn past the causeway).

The layers (beds) of rock are normally named after the location where they were first described, or best exposed e.g. the photo above is the ‘Bobcaygeon Formation’ first identified at Bobcaygeon.

This dates back to the Ordovician period. It can be recognized by its fossils, which were identified by geologists, and published by the Ontario Geological Survey in the 19th Century.

These particular beds are of dolomite (Ca.Mg.2CO3), in contrast to limestone (CaCO3) which is more soluble; a drop of 10% HCl fizzes immediately on limestone, but not on dolomite.

The successive Glaciations each scraped off the top meter or two of the beds, so that afterwards the solution processes began anew on fresh rock surfaces.

|

GEOLOGIC SECTION TO DISPLAY ‘EPIKARST’. This photo illustrates the effects first of steady deposition for a lengthy time on the bed of the Ordovician sea. A thick strong bed, nearly a metre thick, was formed. Then conditions changed to lay down a series of thinner beds above it. These are mechanically weaker and will also dissolve more readily. Typically, each pass of a glacier across such a section removed any weaker top beds of rock, leaving the surface of the underlying thick bed to be attacked by aqueous solution when the vegetation returned. Opened up by solution down any fractures in them, such thick beds form the basis of the ‘epikarst’ (or ‘sub-cutaneous karst’), an uppermost metre or two of the bedrock with highest density of solution voids that drains readily downwards or laterally to springs. While some of the edges of the thin beds are sharp, due to the road cut, most show rounded edges of erosion. |

|

STYLOLITES A stylolite seam is a highly irregular surface that was created by pressure solution during consolidation of the rock under hundreds or thousands of metres of later accumulation. |

|

|

This is an example of limestone pavement (the epikarst) in the early stages of development, before the joint fractures have been much enlarged by solution. This particular surface has been scraped clean by a bulldozer, but the same condition will extend on each side of the road, where tree roots are working down into the cracks to increase the rate of solution or, sometimes, wedge an entire block of rock upwards by osmotic pressure. |

|

VERMICULATIONS Vermiculations, or undisturbed worm tracks, were formed when the original limestone was laid down, |

|

|

The moss is getting a grip into little cavities in the rock. It produces additional CO2 (which causes acidity), which prepares the way for bigger fractures. |

|

CLINTS AND GRIKES A grike is a vertical fracture (joint) in the bed, caused either by shrinkage of the limestone or by lateral compression (shoved from one side). Clints are the undamaged rock surfaces between the grikes, giving the appearance of an array of paving stones |

|

|

This shows a much larger clint surface uninterrupted by grikes. Many patches are like this, with no grike development, because the underlying limestone bed is exceptionally thick and does not fracture so easily. |

ERRATICS

When the glacier scraped most of the surface clean, during recession it dumped ‘glacial erratic blocks’ that it had prised up elsewhere. Some of them have been moved many kilometres. This is an example of a limestone erratic, a local block which probably has not been moved many metres.

The photos are by Heather Ewing, and Ulrich Kretschmar. This text has been edited and approved by Derek Ford, PhD (Oxford), Professor Emeritus at McMaster University and coauthor of a geology textbook, called Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology, published in 2007.

The Common Earthworm – a serious invasive species October 2014

The common earthworm (or Lumbricus terrestris) may be called the nightcrawler, angler worm, or dew worm. Glaciation killed all of the native worms in Canada and earthworm species that are now present arrived with the Europeans less than 2 centuries ago -another invasive species.

This type of worm forms temporary deep burrows

This type of worm forms temporary deep burrows

and comes to the surface to feed. It is said that dew worms can consume all the leaf litter produced in a forest each year.

An earthworm free sugar maple forest typically has a lush and diverse understory, with low vegetation covering more than 75% of the forest floor. When earthworms are abundant, they quickly mix the leaf litter with the mineral soil to form a deep layer of dark topsoil. Most native forest plants, as well as all the animals that live in litter or duff, are not adapted to this altered environment (although it might be nice in gardens). As a result, the forest floor becomes dominated by plants that are well adapted to disturbed soil, such as Glossy Buckthorn and Garlic Mustard. Research in a Midwestern woodland has shown that the invasion by an exotic shrub (Glossy Buckthorn -Rhamnus cathartica ) and the invasion by Eurasian earthworms facilitated one another.

As well, earthworm invasions in forested areas markedly alters the growth of soil fungi (mycorrhizae) that assist the growth of many of our native plants. A mycorrhiza is a mutualistic association between a fungus and the roots of a plant. This relationship provides the fungus with access to carbohydrates such as glucose, produced during photosynthesis, and in return the plant gains the use of the mycelium’s large surface area to absorb water and nutrients (e.g., phosphorus and copper) from the soil. Loss of this association leaves the land available for the growth and spread of invasive alien plants like garlic mustard, which do not depend on the fungal relationship.

The earthworm does not do well in tilled fields because of pesticide exposure and physical injuries from farm equipment. It thrives in fencerows and woodlots and can lead to reductions in native herbaceous and tree re-growth.

These patterns suggest earthworm invasion, rather than non-native plant invasion, is the driving force behind changes in forest plant communities in north eastern North America. Thus, a focus on management of invasive plant species may be insufficient to protect north eastern forest understory species.

Information compiled by Nancy Ironside

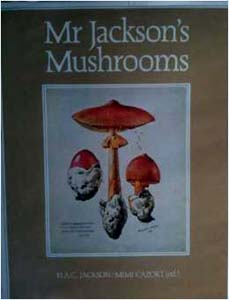

AMANITA JACKSONII SEPTEMBER 2014

These photos show the characteristics of Amanitas -the veil (ring on the stem) and the vulva ( base). Photos depict the development from the button stage to fully mature. It is usually found late summer to early fall.

Amanita jacksonii is a species that was first observed in Awenda Park in 2011 by Hillary Hatzipetrakos, a park employee and mushroom enthusiast.

Within Canada, this species has only been reported at a few localities in southern Ontario and Québec. Following its discovery in Awenda, the Friends of Awenda mandated a mushroom survey of the park to Hillary and Jean-Marc Moncalvo, the ROM’s Senior Curator of Mycology. In 2012 they collected 6 of this rare mushroom in order to study its origin and evolution in Ontario. DNA barcoding will add to the Canadian Barcode of Life Initiative.

It is possible this species has recently expanded its range northwestward as a result of climate change. None of the members of the Mycological Society of Toronto had reported seeing this mushroom in Ontario.

However last year (2013) one of our members, Robert Kokron, an amateur mycologist and photographer, from Midland told us that he found them frequently in all the parks and wooded trails in Midland. He has supplied us with the above photos.

On August 2, 2014 Scott Ercit, of The Canadian Museum of Nature reported that he had found a patch of about 20 in Parry Sound in mixed maple-oak forest in Parry Sound.

Why in this area? Is it the deep snowfall, or the lake effect. This fungus looks very similar to the southern European Amanita Caesarea -apparently a favourite of the Emperor.

Robert Kokron of Midland provided these beautiful photos as well as range and frequency information.

H.A.C. Jackson was born in Montreal in 1877, the eldest of six children

H.A.C. Jackson was born in Montreal in 1877, the eldest of six children

One of his siblings was A.Y. Jackson, of Group of 7 fame. H.A.C. left school at fourteen to help provide for his family, finding work as a commercial artist.

He had a passion and talent as an amateur mycologist and botanical artist, as was demonstrated in this book. The cover painting is Amanita jacksonii. Having a beautiful, delicious and rare mushroom named after him-a great honour-gave him recognition in the mycological world.

INSECTS ON MILKWEED LEAVES AUGUST 2014

3 milkweed insects will be presented with their strategies in dealing with the latex

of the milkweed leaves

MONARCH BUTTERFLY CATERPILLAR – DANAUS PLEXIPPUS

These caterpillars are found on young vigorously growing leaves-old leaves are ignored by caterpillars.

These caterpillars are found on young vigorously growing leaves-old leaves are ignored by caterpillars.

They appear to chomp up the latex, and make use of the cardiac glycosides (heart toxins) from the leaves they consume. This carries forward to the butterfly, protecting them from predators, who appears to recognize their toxicity.

MILKWEED TUSSOCK MOTH –ARCTIIDAE : EUCHAETES EGLE

They do not compete with the monarch caterpillars, since they are content to eat older foliage. They feed in groups of up 50, and can completely wipe out a milkweed plant, leaving only the skeleton. They avoid the latex by eating between the veins.

MILKWEED LONGHORN BEETLE – COLEOPTERA -CERAMBYCIDAE: TETRAOPES BASALIS

A milkweed leaf with a notched tip is a characteristic feeding sign of an adult milkweed longhorn. the midrib has been nipped

to cut off the flow of latex. With this sticky defense disabled the beetle is free to eat the leaf without fear of getting gummed up jaws.

(The larvae enter the stems close to the ground, and bore down and feed on the roots.)

SMALL MILKWEED BUG –HEMIPTERA – LYGAEUS KALMII

“Bugs” and “beetles” are confusing in nomenclature. But they even belong

“Bugs” and “beetles” are confusing in nomenclature. But they even belong

to different families (Hemiptera and Coleoptera)

Among other ways to tell them apart is the beetle’s wing covers meet in a straight line down the middle of the back when closed, whereas the bug’s wings and covers meet in a sort of diamond, or cross hatch fashion.

Although this is a Milkweed insect, it grows on the seed pods and flower heads, so it neither deals with nor avoids the latex. These are considered “seed bugs”. After the first frost, they hibernate in plant debris, small logs.

We only found one example of this.

Photos of the Milkweed Tussock Moth were taken on Aug 9 by Denis Paccagnella in Carolyn’s garden.

The other photos were taken Aug14 by Nancy Ironside, mostly at the garden at the quarry (Uhthoff Trail).

References: Caterpillars of Eastern North America by David Wagner

Tracks and signs of insects and other invertebrates, by Charley Eiseman and Noah Charney

BLUE-SPOTTED SALAMANDER Ambystoma laterale JULY 2014

The Year of the Salamander

Wow, this year I have seen more Salamanders than any other year and all in my own front yard. We have seen at least a dozen in the last few months. Every few weeks another one is on our driveway or front lawn.

Some as big as 5 inches.

Now the question is, are they Blue Spotted Salamanders, Jefferson Salamanders or they could be a hybrid of both the Jefferson and the Blue Spotted. They cannot be reliably distinguished without a genetic test.

Briefly, if viewing the pure genetic specimens, the Blue Spotted is generally smaller, 3-5 inches, and darker than the Jefferson with bluish spots on the sides and its vent is usually black. The Blue Spotted inhabit a wide variety of woodland habitats but a pond that retains water is essential.

The Jefferson is 4-8 inches, and is brown or grey not black on the back with a paler belly and with gray colour around the vent. The Jefferson prefer undisturbed deciduous woodlands.

At our house the moisture requirement was being met by a wet mat left on a cement slab, where we found 2 under the mat.

Here is a link that describes their differences and their unusual mysterious biology. http://www.ontarionature.org/protect/species/reptiles_and_amphibians/blue-spotted_salamander.php

Some individuals have more blue spotting than others.

Photos and report from Barb Ryckman. She is living near Lake Simcoe, near Hawkestone.

BLACK-BILLED CUCKOOS AND EASTERN TENT CATERPILLARS JUNE 2014

|

Both have similar traits – eat hairy and spiny caterpillars, and are occasionally parasitic, laying their eggs in nests of their own species, and occasionally others, such as the Black-billed Cuckoo. |

The Eastern Tent Caterpillar ( Malacosoma americanum) is an unloved species, but an important part of the food chain. It spins a communal nest in the crotch of a tree between 2 or more branches. This year they are uncommon in our area, but apparently in Alberta and the north eastern USA there is an outbreak of “biblical” proportions.

(The Forest Tent Caterpillars are similar, and gregarious, but do not spin a tent. According to John Challis in Washago, there is a growing influx of forest tent caterpillars in his area and he can hear the soft rain of their droppings in the woods, when it is still.)

The abundance of Black-billed Cuckoos (Coccyzus erythropthalmus) mirrors the outbreaks of tent caterpillars, as well as of Spruce Budworm, Gypsy Moths, and other irruptive species. But how do cuckoos cope with the toxic spines of these hairy caterpillars? Stomach contents of individual cuckoos may contain more than 100 large caterpillars or several hundred of the smaller species. The bristly spines of hairy caterpillars pierce the cuckoo’s stomach lining giving it a furry coating. When the mass obstructs digestion, the entire stomach lining is sloughed off and is regurgitated as a pellet.

This is a remarkable adaptation.

Other birds, such as orioles, jays, chickadees and nuthatches may also eat caterpillars with toxic spines, but not in the numbers that cuckoos eat. Some have observed jays shaking the caterpillars to try to dislodge

the spines before consuming them.

Fortunately Arni Stinnissen has taken wonderful photos of Black-billed and Yellow-billed Cuckoo, (and the Baltimore Oriole, not shown ) feeding on a tent caterpillar nest, which he is sharing with us.

For those interested in more interesting facts about Black-billed Cuckoos, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology provides an online bird guide at www.birds.cornell.edu/, and is a useful resource.

Pale/ Pink Corydalis – Corydalis sempervirens May 2014

This is a characteristic plant of granite rocks on the Shield. It also grows on disturbed sites, and especially after a fire. It is related to Bleeding heart, and Dutchman’s-breeches. Other delicate looking corydalis species have yellow flowers, but this type has pale pink flowers, with yellow lips, and a bulbous base. The leaves have a whitish bloom. The pods are long and slender, as shown in the photo, upper right. It is common where found, rare where not found; but it is often overlooked.

Photos by Heather Ewing, taken May25 and May 31/14.

Text by Nancy Ironside

Washago’s Barrow’s Goldeneye April 2014

In most winters, the only reason photographers visit Washago is to capture images of trains steaming in the cold. But in the late winter of 2014, birders and photographers from across southern Ontario showed up to pick out a striking make Barrow’s Goldeneye. Local photographer Arni Stinnessen was able to get a great shot showing the differences in plumage between this rare visitor and Common Goldeneye.

Most Barrow’s Goldeneyes nest in ponds and wooded lakes in British Columbia, Yukon and southern Alaska, with a few in northern Labrador and Iceland. They winter in coastal estuaries, so are known as sea ducks.

In fact, they are one of the species most affected by the oil spill from the Exxon Valdez. So what is one of these sea ducks doing in Washago?

In fact, there are usually a few winter vagrant Barrow’s Goldeneye that show up each year in the Great Lakes or the Ottawa River. This year, an abnormally cold winter caused Georgian Bay and Lake Huron to freeze into solid ice cover, causing some of the winter ducks to head inland to small patches of open water. One of those open water refuges was at the northern tip of Lake Couchiching, where a constant flow of exiting water keeps ice at bay.

This March, about 4-500 Common Goldeneyes jammed into this open patch each evening at dusk. Among these hundreds of milling, diving, displaying Goldeneyes, one bird was different – more black on the back and shoulder, a white crescent on the cheek rather than a round spot, a head more rounded than peaked.

That was the Barrow’s Goldeneye, and each evening a sparse and shivering group of birders played “where’s Waldo?” to find it among the melee.

Text by Ron Reid, Photos by Arni Stinnissen

Mourning Doves Target Practice March 2014

Environment Canada is allowing a Mourning Dove hunt in central and southern Ontario. For 70 days, from early September to mid November, hunters with licenses can kill 15 doves a day, and have 45 in their possession. This change was not widely publicized, except among hunters.

The repetitive mournful song of the Mourning Dove (and symbol of peace) gives us hope that spring is coming, even though the snow cover this year tells us that it is not.

The Mourning Dove has been increasing its numbers and range for several decades. Recent breeding population estimates about 1.3 million birds in the spring.

People react to this controversial news in their own ways.

Hunters are happy, given that they have been asking to hunt doves for years, and, especially in the last 5 years, they have lobbied with the Canadian Wildlife Service, who have concluded that the hunt was biologically justifiable, given the population. The study was done by Scott Petrie, executive director of Long Point Waterfowl, and funded by the OFAH. More than 20 million Mourning Doves are killed each year in the US, (in the 40 states in the Midwest, where it is legal). They say they are excellent grilled, broiled or roasted. This is a good way for new hunters to get involved. While they are difficult to hit mid air, they are less wary

than other birds on the ground. They also report that hunters in wheelchairs are really excited about this opportunity.

Non-hunting Nature lovers cannot understand the mindset around why one would want to hunt these (according to Caroline Schultz of Ontario Nature). She acknowledges that the hunt is not expected to devastate the population. But in most cities, and Orillia, municipal bylaws prevent shooting the birds in city backyards, so we are safe at home.

Feeder watchers have mixed opinions –they think Mourning Doves eat a lot, poop a lot, and don’t do much but mourn, and mate. A chickadee hunt would bring a totally different response.

Activists are mounting a campaign, but there is little support. Few people other than hunters know about the new law.

Vegetarians are not involved –they don’t eat meat anyway, and at least these birds are not kept in cages in substandard conditions (eg chickens).

The birds? They probably don’t know that the law has changed, and, given the dwindling population of hunters, they may never know.

Dutch Elm Disease February 2014

Healthy looking elms in our area ( Orillia and Mara townships)

Those of us of a certain age remember the elms in shady tree-lined streets and farm roads –a dense canopy, forming an arch. These were the perfect trees to plant (shade, windbreak), which did not interfere with power lines, and they might last 300 years.

All this changed in the 40s, 50s and 60s. They died.

They became infected by a fungus called Ophiostoma sp., an ascomycete, indentified by 7 outstanding Dutch women scientists, so we now call this Dutch Elm Disease, although it probably originated in Asia.

The fungus is dispersed by the Elm Bark Beetle, which tunnel into the inner bark to overwinter, lay their eggs, which form larvae which feed on the inner bark (forming “galleries”), then emerge as the beetle which carries the Dutch elm disease spores to nearby elms on their bodies. The Elm must be large enough, with irregular bark, to support breeding beetles before it is infected.

The disease can also spread through root systems to trees that are within about 50 feet.

But there are some beautiful vase shaped healthy elm trees in fields in the country around here, with their classical silhouette, which is especially noticeable in the winter. These trees grow alone, were probably not planted by farmers looking for shade and windbreaks, and may be the salvation of the much loved White (American) Elm.

Are they protected by their distance from other elms (away from beetles and root interactions) or do they have some immune system resistance, which could be propogated by taking cuttings?

Studies are taking place at the University of Guelph, but their success will be measured in decades, not months.

The American elm, which has been decimated all through its range by the ravages of Dutch elm disease, is alive and thriving in Central Park , New York City. The New York Times had a photo of the thriving Elms in Central Park this winter. Why are theirs ok and not ours? According to the internet Winnipeg still has stands and Saskatoon is disease free.

A Buffet for a Cooper’s Hawk January 2014

Arni writes from Sundial Drive in Orillia:

Each year I put up a variety of feeders that usually attracts a wide variety of birds during the winter. Like most feeders, we also get the occasional visit from a species that is higher in the bird food chain, the Cooper’s Hawk. This year, my feeders are unusually quiet with just a few Black-capped Chickadees, Dark-eyed Juncos and an inordinate number of Mourning Doves. I think that the feeders are even quieter this year because the Cooper’s Hawk seems to have taken up permanent residence in our backyard perching high in a Popular Tree or sitting stealthily in the White Spruce.

I have yet to see a successful strike but I often see feathers flying around.

The Cooper’s Hawk looks similar to the smaller Sharp-shinned Hawk but has distinguishing features such as the dark grey or black cap and long, thin, banded and rounded tail.

Thanks to Arni Stinnissen for the photos and report